It only takes only a few moments of careless inspection to see it. It has existed since the beginning of time. It is what binds all humans together yet creates distinct and distasteful boundaries under which we are repelled from one another. The universal topic of philosophical thought; ubiquitous in all questions. No matter what set of beliefs one holds, there is one thing to be sure, and perhaps one of the only things: the world we exist in doesn’t function properly. In Augustinian terms, “evil” certainly does exist in our world. Religion and philosophy alike try to put reason behind why the world is corrupted and how we can understand this corruption, since that is the only experience we hold. If there was something as ideal goodness, we could not comprehend it considering we have no comparison, having only experienced a less-than-good world. Augustine explains in his Confessions the reason behind our fallen world; why there is the concept of evil. He says that God, who is a perfect being, created man and the world, also perfect. However, when sin contaminated the world, it created a string of improper relationships in the world, that is things interacting contrary to how God intended them to. As Christians, our goal is to come back to the proper relation we had with God and creation before sin entered the world. Augustine sees the relationship between Creator and Creation after the Fall as a complex mixture of the original good God intended and the sin-contaminated interactions between them.

The first aspect to look at when dealing with the problem of evil is establishing what evil is to begin with, where did it come from, and so on. Again, this is an onslaught of philosophical problems and abstract terms. Augustine, however, quite clearly defines evil in the context of good, reaching his definition through several logical steps. First he notes that God created all things, and everything he created was good. Since we understand evil to be, perhaps, the polar opposite of good, it therefore cannot be a ‘thing’ at all, otherwise God put evil in the world, contradicting the first two premises. The next questions that Augustine follows with is, “Where, then, is Evil...?” (Bk. VII, 5.7). Augustine argues that evil is not material at all, nor is good. Rather both are entities that exist in the essence and context of material, that is how material is used. The articulation of evil is solely based on the quantity of good within the material, evil then, being a relative term.

This concept may be hard to comprehend, however, the nature of light and darkness effectively communicates the parallel nature of good and evil. Light and darkness, both being non-physical, in a tangible sense, are yet detectible entities and exist under human visual senses, yet are invisible to all of our other senses. In a similar way, humans can detect good and evil, perhaps not through any neurological sense, but rather a moral sensory device, noted by no scientific evidence. Also, darkness cannot exist without the acknowledgement of light and vice-versa. Yet darkness only can exist without light, or is defined by “the absence of light”. Evil also exists in the absence of good, being defined in Augustine’s words as “...evil is nothing but the diminishment of good to the point where nothing at all is left” (Bk. VII 7.12).

Augustine, desperate for answers to the problem of evil in our material world then asks, “...where does it come from and how does it creep in?” (Bk. VII, 5.7). Surely evil though it may not be a ‘thing’, stems from absolutely no root. To properly consider evil’s true origin, Augustine traces it back to its birth: the Fall. He notes how the Fall was again, not begun by any evil object, for everything God created in the Garden was truly good, but rather the Serpent’s persuasion and the choice man was given. After pondering the mysteries of the Fall, and how humanity became imperfect beings influenced by evil he sources “...the cause of evil is the free decision of our will...”(Bk. VII, 5). It is not the actions themselves not the results they may cause that are evil, for they are only the victims of human defected will (the term voluntarius defectus is used in Ch. IV of Augustine’s Enchiridion). Humans have corrupted will in that they do not submit in obedience to the higher power who created them as they were designed. Instead, we exist in a state of constant rebellion to a force that we can and will never overcome.

Now that the source of evil is identified, it is for man to determine where good is and to align himself accordingly with it. In order to understand how Augustine would determine this. Firstly, goodness should be understood in Augustine’s terms, the way to goodness is the same way to Truth. Augustine considers goodness is a mere stem of Truth, and Truth is parallel with God. Therefore, all good things, or all things, have elements of Truth, but not all of Truth exists within each individual thing. This is a gateway to whole other philosophical study, that being the pursuit of Truth, but also drives Augustine’s audience to inquire what the essence of man is and how man can extract goodness from a fallen world. Augustine’s understanding of philosophical ideas and general Epistemology moves from a Manichean ideology to a Neo-Platonist’s perspective in the context of Christianity. A Manichee sees the world as fallen as well, but not by mere defected will, but everything in it being evil. Augustine’s language strongly reflects his distaste of this idea, provided that at the time of writing he believes all Creation to be good. After abandoning Manicheism, Augustine’s post conversion philosophy shows quite strong Platonic sympathies. In reference to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, Augustine explains the nature of reality. The key to understanding Augustinian Epistemology and how Augustine views the material world is in understanding the Platonic concepts demonstrated in the Allegory of the Cave.

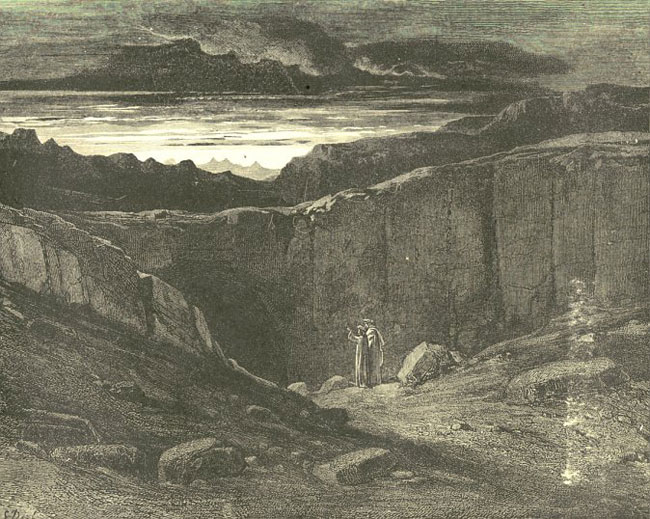

Through Plato’s ideas, Augustine accounts for reality among the material we live in. He highlights the points of the Allegory of the Cave, creating a parallel to a Christian theology. Here, Augustine sets a Platonic standard that is closely kept throughout the Medieval and Renaissance Church, as can be seen later in the writings of Thomas Aquinas and Dante Alighieri. The significance of Plato’s influence on the Church through Augustine during this time period is key to understanding the shifts the church went through at this time. In the Allegory of the Cave, men are bound to face a wall of shadows, imitations of their true forms. These shadows, while they are not as “real”, or in Augustinian terms as “good”, as the original true form, they reflect parts of it, and thus are not the ‘unreal’ or ‘evil’, but rather they are faded forms. In Augustine’s terms, these imitating forms that we interact with on earth are considered to be “the lowest kinds of goods”(Bk. II, 5,10). The prisoners chained to the wall of the cave, having only been taught that they shadows they see are true, in Augustine’s words “turn away from the better and higher [goods]” (Bk. II, 5,10). However, due to our lack of contact with the greater goods, we are unable to understand the scale of goodness and “these lowest goods hold delights for us indeed” (Bk. II, 5,10). Humans confuse the lesser goods, which we desire because of the aspects within it pointing toward the greater goods, with the greater goods themselves. Or in Plato’s terms, the prisoner finds beauty and truth within the shadows cast upon the wall because they see part of the beauty and truth in the shadows that exist in the world outside. Augustine says that men “distort Truth into a lie and worship and serve the creature instead of the creator”(Bk. V, 5).

Even though the world that exists around us is good to some extent, it surely cannot be the only means by which we perceive true goodness. Trying to understand Truth through material is as difficult as trying to fully imagine a painting with only exposure to a square inch of it. The often conflicting free-wills of humans who attempt coexistence in the world are indeed corrupt (as men naturally are), and we are to “shape ourselves no longer to the standards of this world, but rather restrain ourselves from it”(Bk. XIII, 30), noting that we should not isolate ourselves from it. If we were meant to completely isolate ourselves from the world, we would have no sensual access to God’s goodness through his Creation. Since we are human, we have a great deal of reliance of the material, rational experience, because we have become “servants of reason”(Bk. XII, 31). God’s encouragement to retain a degree of contact with the world is evident in the reincarnation of Christ, which otherwise would’ve been completely pointless. If we were to rely solely on irrational faith, then we would’ve never been created into physical existence in his Creation to begin with. God very specifically intended the physical, material world we live in and created us to be rational beings to understand the material around us. Since we understand truth in a rational way, he sent Christ as a means of sensual and rational connection. Had we been created to only account for God on a rational level, the miracles Jesus performed would have been only a mystery and the breath of God amid the world would be nonexistent and invisible. It is in our individual lives we are to account for both God’s rational, through the material world, and irrational, through faith, communication and decide how we will control our loose free will.

Augustine demonstrates through the Confessions the complex relationship between God, man, and the world. He presents God as being the innate-known ideal goal after whom man pursues, all men having a desire for Truth and an understanding of evil. The Platonic forms he refers to reflects the nature of God and how the world appears good to us. It is through the material world that we were designed to know God. However, through our defected will, we deny God’s superiority and often live our lives in futile disobedience. This corruption is evil and therefore, we confuse the world, the means by which we reach the goal, with the goal itself, creating an ambiguous journey for man which God actively tries to clarify through the events in our lives.